Date

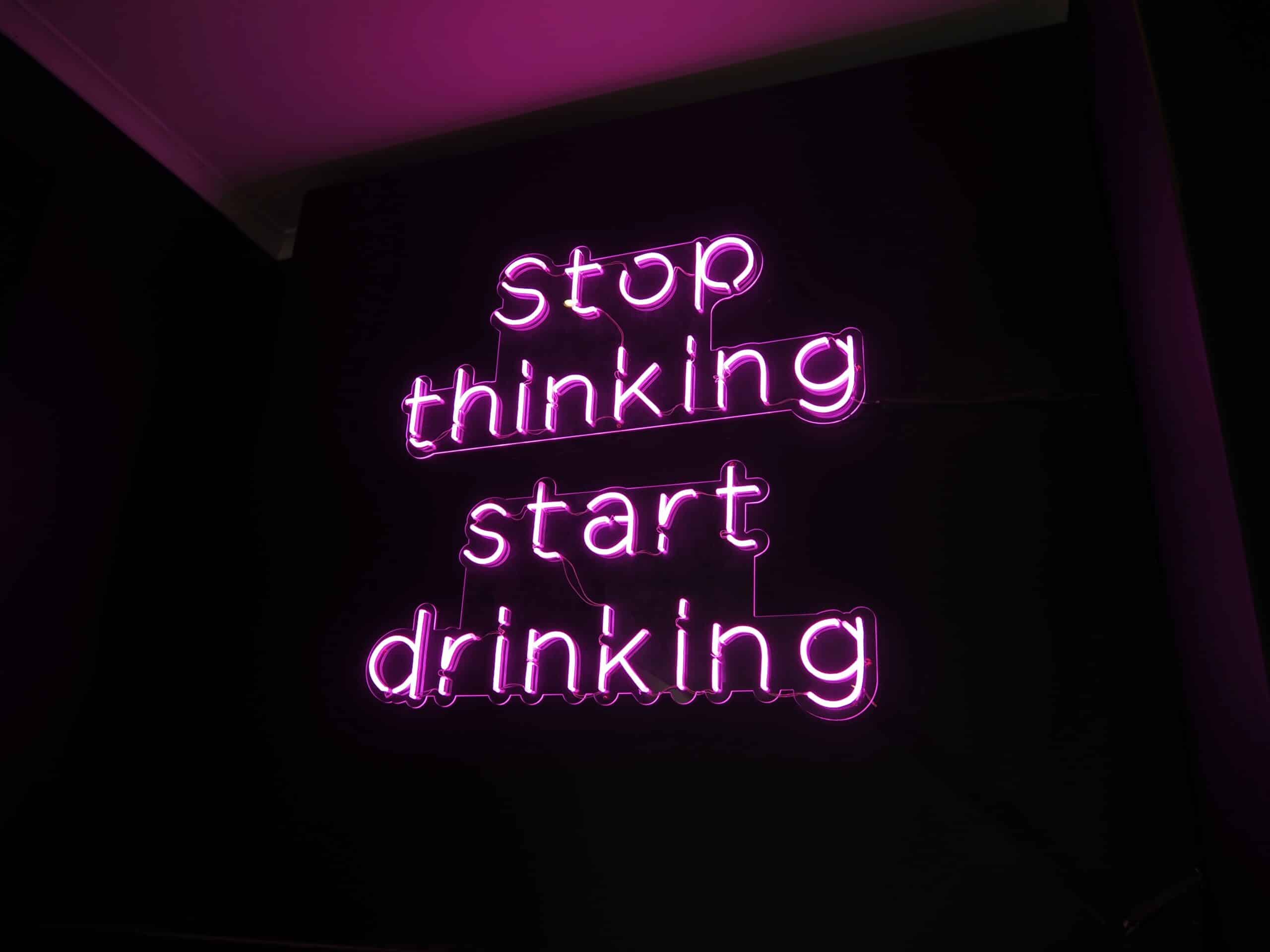

What ‘smuggled’ booze says about capitalism, coping theatre, and the cost of performance.

Let’s call her L, she is in late 30s, a doctor. A woman who advises others how to regulate, heal, and function better. She arrived at the retreat with journals, supplements, a schedule cleared for “getting back to herself.”

She also smuggled in whisky and gin, tucked deep into her bag like contraband.

This is not allowed. We’re clear about it. No alcohol.It is not because we’re taking a moral high ground, but because we didn’t sign up to manage drunk people. And because we aim to create a space for real pause, for actual rest, that can’t happen when your body is being flooded with ethanol. You’d think 72 hours without a drink wouldn’t be that hard.

But she drank, in her room. Slipped into meals late. Disappeared again.

And here’s the thing: this isn’t rare. It’s disturbingly familiar. Especially among high-functioning, high-achieving women and men. It’s certainly not the first time, and not the only time, we’ve seen this unfold. It’s not because they’re reckless. But because they’re tired. Because alcohol is the one socially acceptable crack in the mask and a way to cope. A way to regulate just enough to keep performing. As sociologist Carol Emslie put it:

“You’re not allowed to break, but you’re allowed to drink.”

This is how it works. Alcohol doesn’t show up as collapse, it shows up as a treat.A “well-earned glass of wine”, a cheeky reward, a lifestyle hack.

From the outside, it’s pleasure. Inside, it’s management. Quiet coping. Emotional anaesthetic with a nice label.

L didn’t break our rules because she’s selfish. She broke them because our culture makes not drinking for three days feel radical. Even suspicious. It’s why “Dry January” needs a campaign, but drinking every night doesn’t. We choose to drink but we’re not as free as we think. Choice is shaped, marketed, neurologically reinforced.

And yes, deciding to keep this place alcohol-free makes us awkward. Like we’re breaking some unspoken social contract that says a glass of wine is harmless, even expected. When you go out for a weekend in nature, when you decide to take time off work to retreat, alcohol is often assumed to be part of the package. But that’s the point, it’s so expected, it’s hard to question. Even for 72 hours.

L showed us something. Not failure but a perfect expression of a system that asks people to work hard, to achieve, to be productive, to stay regulated and to look good doing it. And when it gets too much? Well, pour a drink. Reset the reward circuitry. Mask the fatigue.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote about this long before self-care became a brand:

“When this becomes unbearable, substances offer a private protest, a momentary refusal to perform.”

There’s no neat ending here. There’s no judgement. Just a question.

What does it mean that we live in a world where a woman who advises on health, or others who drank ’secretly’ here, can’t go 72 hours without a drink?

We’d love to hear your thoughts. Have you noticed similar contradictions in yourself or others? What do you think keeps alcohol so embedded in how we rest, retreat, or reconnect? Send us your thoughts.